We photographers like to work early and late in the day. For many people, getting up early – really early – is difficult (to say the least!). Luckily, I’m pretty much a morning type person. As far as I’m concerned, 9:00 PM is almost the middle of the night.

Here are three frames, taken a week ago, at about 5:00 AM. These are from a small lake I’ve been working. All three frames were shot from the same location, with my Nikon D4 handheld at ISO 1600, and the new Nikon 80-400mm lens. Just in passing, I’m very impressed with this lens, to the point that I’m thinking about selling my Nikon 200-400mm f/4 if anyone’s interested.

Adobe Creative Cloud

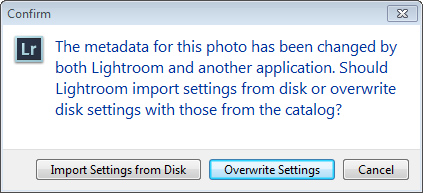

If you’re a Photoshop user, you’ve undoubtedly heard about the Adobe announcement that from now on all new versions of Photoshop will be by subscription only. You download the software, and it resides on your computer, but if you don’t pay the subscription fee the software deactivates. Potentially this means that you might not be able to access your images. Subscribe for a while, save a master layered image, and only by paying the subscription fee can you get back in to work with that layered file. Yes, it’s on your computer, but of no use. In short, it seems to me you have two choices: (1) pay the subscription fee, and keep paying it forever, even with price increases; or (2) stick with PS CS6, the current version which you can purchase outright. The problem with (2) is what happens if you buy a new camera, not supported by CS6, or get a new computer with a new operating system on which CS6 will not run? You could keep your current gear, but I for one am certainly not at the point of saying that the cameras and computers I presently own are my final cameras and computers.

Adobe has different pricing schemes, and for those who use multiple Adobe products the cost per month makes some sense. But I don’t. I use Photoshop, and occasionally InDesign, and the latter is an older version which I have no plans to upgrade.

Like many, I’m not happy about Adobe’s decision.

But…there is a small glimmer of hope, especially if you’re a Lightroom user. Lightroom was designed specifically for photographers, while Photoshop was not. Here’s a long forum piece which in my opinion is well worth a read:

http://www.luminous-landscape.com/forum/index.php?topic=78240.0

In case you don’t know the players, Thomas Knoll is the original creator of Photoshop, Eric Chan is the chief engineer on Adobe Camera Raw, and Jeff Schewe is a photographer/developer closely connected to Adobe.